Comet Ferron Headed This Way

Elusive Folk Legend Ferron Comes Blazing In

by Gary Alexander

Preview of Ferron

at Catskill Mountain Coffee House

Fri, October 6

Rt 28, Kingston, 845-334-8455

|

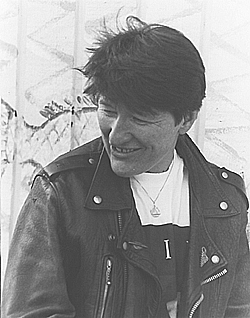

Photographer: Saul Rosenthal

|

You

know where to look in the sky on a clear night to locate a

particular star just as you can chart the career course of a

mainstream entertainer without undue bother. Artists outside of the

corporate mainstream, however, even as they periodically issue

superior bursts of talent, can present difficulties to those hoping to

track their progress akin to following the course of a comet;

disappearing entirely for extended periods and leaving you with only

those snapshots you managed to snatch when their orbits bring them

into view.

Evasive and exquisite, the songs of the woman called Ferron can be as

startling and rare as a luna moth on a screen door. All but a couple

of her eleven elusive albums are out-of-print and those few which are

still available require determined effort to secure. The conspiracy

of circumstances which has rendered these few recordings so difficult

to obtain may be remedied for local fans by her first appearance here

in decades, at the Catskill Mountain Coffee House on Route 28 on

October 6th, and the recent release of a double-cd retrospective on

her own label selected from a career which spans 30 years of

songwriting and 25 of touring. For those who have struggled to stay

abreast of her creative output through small label trickles and

out-of-circulation mysteries, the album is a dream come true.

Photo by Ray G. Ring IV

Photo by Ray G. Ring IV

|

"It's time," said Ferron from her home on a small island near Seattle.

"After 30 years, you'd think I probably have a right to talk a little

bit about what I was doing."

And so she does, in a 24 page booklet packaged with the CDS, offering

a verbal slide show of the interior Ferron (who adopted the name from

a friend's dream and legalized it); glimpses of a journey frequently

obscured to outside view by distance and occasion.

Born the eldest of seven children in a working class family outside

Vancouver, a suburb which, she notes with a sigh, "is now its own city.

It used to be just farmland. That's how much things have changed."

Ferron left home at 15 to support herself through a decade of factory

work, waitressing, cab driving, and other less-than-glamorous roles

before recording her own "basement tape album" called

Ferron which she

self-distributed in 1977. This was followed up with another in 78,

Ferron Backed Up, as she attempted to build a career in the limited

and somewhat cloistered arena of the contemporary Canadian music

scene.

Being Canadian was the first uphill step to expanding her horizons

into the U.S. market.

"I have a green card, so I actually live in the States," said Ferron,

who was packing in Seattle to leave for one of her usual winter stays

in the Philadelphia area when the phone rang.

"But, before that, you

would have to apply for a time period. If you knew you had a show

March 16 and you knew you were going to have your last show of a tour

on June 7th, say, you would apply to have permission to work during

that period of time. What was unfortunate about that was sometimes

it's pretty hairy and right near the end of a planning schedule is when

things solidify but you would have had to apply long before actually

knowing everything. So, you couldn t take any outside dates."

Such was Ferron's situation as a Canadian citizen with a searing

endowment of creative proficiency that possessed its own will to defy

borders. It was just the first hurdle.

Word of an immense new talent began seep into wider distribution with

the release of

Testimony in 1980 and

Shadows On A Dime in 1984, issued

on the U.S.-distributed (but still relatively small) Lucy Records

label and a four-star rating for the latter from

Rolling Stone. Both

of these albums are sampled on the new cd,

Impressionistic Ferron, and

admirably demonstrate that someone early on had the ear to enlist a

crew of superb musicians to compliment Ferron's earnest and

sophisticated deliveries and the persistence to insist they be allowed

to "breathe" on the tracks. Looking over the consistent quality of

accompaniment across her quilt work career, you'd have to think

Ferron, herself, had a hand in it in as much as the heady

sensibilities of the arrangements are related too intimately to the

individual songs structure and performance to be too far removed from

the artist's concepts.

After a decision to withdraw for a period of circumspection and

writing in 1986, ("I just wanted to go 'back in' and not be so

'out in

the world'.") Ferron signed with the Chameleon label and recorded

Phantom Center, which was delayed by the company's internal

tangles ("They changed horses in midstream.") until 1990. Shortly after that

the label crashed to earth with a soundless thud. About the time the

original and somewhat overproduced version of this still strongly

written album made the rounds (later to be rescued in a remixed

rendering of the tracks which brought the production-smothered artist

back to the surface and released by Earthbeat/Warner Brothers in a

package deal which included her legendary 1994

Driver and Still Riot,

which she recorded for Warner in 1996), Ferron began working on an

instrumental album (Resting With the Question, 1992) through a process

which, consciously or not, reacclimated her sensibilities to the

purest core of their own undoctored musical forms.

"It wasn't very fancy or anything; the kind of music that people use to

massage by, now," Ferron recalls with a bit of a smirk in her tone. "At

the time all I was trying to do was to find a place where you could

hear music and not have a thought. If I hear particular chords, I

immediately have an emotional reaction, which is higher and lower.

It's like I'm being moved around in my feelings. I was kind of trying to

see what it would look like if there was a center-place where you

didn't do that when you listened to music. You didn't have any particular

memory or charged moments."

Composed on a keyboard in a stretch of time during which she may have

felt a little numbed by the overbearingly pop mechanizations heaped on

her most recent melodies, Ferron describes the effort as coming "during

a period when I just really wasn't sure what I was thinking about or

what there was to think about; a kind of lull in consciousness."

Referring to the music as "sort of mesmerizing," she explains "I would

write these little pieces and then go back and put it (sic) on a loop

and listen to it for hours on hours and, while I was listening, if any

section stuck out at all, I would change it...It's kind of stupid when

I think of it now," she laughs. "I think it was like an exercise."

It might also be seen as a reflexive demonstration of skill to balance

impressions of a performer whose lyrical abilities have been

celebrated and emphasized over the musical ingredient of the work but

on closer inspection the dreamy, rhythmic and "mesmerizing" qualities of

her ballads, even early on, display close attention to this attribute.

If this effort didn't garner the attention it may have deserved, it

probably was due to the absence of her line sculpture, so above the

common fray of poetry in popular music, which beguiles with tilted

perspective to sink in and seize notice. Lines like "We are footprints

and handprints and knees in the dew" reach out to stun you but would

not register so forcefully without Ferron's deeply seated musical

sentience; a plaintive laidback urgency; which allows her to

convincingly transport an unlikely line like "Oh my planet, oh my

present that ever unfurls" in measured soulful tones.

Another clue to Ferron s determined motivations might be gleaned from

a brief review of a July 1996 show at the Bottom Line in New York City

contributed to the website

FerronWeb.com by a fan. In a round robin

scenario with Dar Williams, Cheryl Wheeler and Heather Eatman, the fan

reports: "For the finale the host asked each woman to perform a cover.

Ferron, saying she didn t want to sound arrogant, but simply never

learned music in a traditional sense, didn't know any covers. So she

broke from the pack and did an amazing acappella version of

'Sunken City'."

As for "music in a traditional sense," Ferron's guitar work is evident

and exquisite on the live cuts sampled on Impressionistic Ferron, but

could we surmise from experiences such as this that her reaction to

some self-perceived musical deficiency was a spur to her decision to

record an entire album of covers (Inside Out) in 1999?

Ferron was living at the Institute for Musical Arts in California and

teaching writing workshops when she noticed a particular deficiency in

the students' musical experience; "I discovered they didn't even know

little songs like 'Walk Away Renee' and various other tunes that I

really loved. June Millington was there as well and she's very

passionate about that whole era of music and so the next thing we

thought was we should just go and get these tunes."

And, ah ha!, there was another level to the resolution... "Part of it

for me was that I never really learned music. I just kind of eke it

out, whatever it is I need to hear. If I play with a band or if I m

creating a song, I have an idea of something but it s not theoretical.

I just keep at it till I get it," Ferron said. "So, it was exciting to

me to go back and see how these tunes were constructed, since they

seemed completely unattainable to me all my life and some of them are

amazingly complicated...say, for instance, 'What Becomes of the

Broken-Hearted', which I found incredibly difficult to sing; not

because of the melody but because of the rhythm- in that you're just

barely getting a chance to breathe and the song just moves through.

It was really exciting to really sort of be on that edge and wonder if

they had sung the song all the way through when they recorded it

or...They probably did. They wouldn't have been punching in and out

everywhere..."

The moral of the story is that Ferron sensed a space to elevate and

develop in a craft in which she was already considered masterful and

moved in on it.

Ferron (left) with Greg Brown and Cheryl Wheeler in a

Ferron (left) with Greg Brown and Cheryl Wheeler in a

songwriter

round robin at Falcon Ridge Folk Festival, July 1999

Photo by Ray G. Ring IV

|

As for covers of her own music, if you look, you'll find them. Greg

Brown and Bill Morrissey team up for a delicious version of the

bittersweet Ferron classic of parting ways, "Ain't Life A Brook." In a

just world, that tune would have been a smash hit. But major label

promoters and a majority of radio stations never seem to have

"hit" and

"folk" in the same thoughtstream these days. Not since the days

folkrock scared the Establishment whitelipped.

"Indigo Girls, Sweet Honey In the Rock, Holly Near," Ferron recites

among the artists who have covered her songs. "No one 'bankable'. No

one commercial. Just our kind of person, moving around, doing their

work. No big magic tricks."

There's one answer for those who may now be saying, "Well, if she s so

good, why haven't I heard of her?" Another which might be considered

is a companion difficulty of distribution: Category.

A live album called

Not A Still Life, also issued in 92, featuring

just the woman and guitar, gave a cue to the

New York Times reviewer

who referred to Ferron as a "nomadic folkie" and "One of the most

respected Canadian folk performers in more than a decade" while

reviewing her

Driver album of 1994. But the latter album itself, also

sampled on the new cd, requires a gymnastic stretch to classify as

"folk". Therein lies the rub.

"I was with Chameleon in the early '90s. Then I went with Earthbeat

down in California," Ferron explains, retracing her nomadic recording

career. "Then they handed me over to Warner Brothers and everybody's

whole thing is- 'It's about promotion.' But that's not a thing that

anybody knows how to do. It's got a bit of a trick to it because,

unless you have something that is so undeniably noticeable that you re

going to be able to generate a whole bunch of money right away-

basically the promotion money comes from the money generated- they

give you about a six or ten week window. If it doesn't happen,

everybody starts backing off to their corner."

This would seem to be a reference to her experiences with her Warner

Brothers mainstream release in 1996, Still Riot. This is one of the

few of her albums still available and well worth seeking out. If a

full collection of her catalog ever assembles next to my player, I d

take that as a challenge to find a venue for a song-by-song appraisal

which space here forbids but, alas, like so many Ferron enthusiasts, I

continue to toil upon the road and surf upon the web in quest of those

musical grails absent from my clutches; those glittering but feebly

promoted gems so swiftly in and out of print which never show up in

"folk" bins nearby. Woe is me...

How do you promote a non-folk "folk album?" It's "Americana," it's the

unwieldy "singer-songwriter" thing, it's "New Wave Folk", it's

"Neofolk," it's "Women's Music"

(which is commonly ill-defined as being more about

"women than it is about music.") None of this quite fits Ferron.

There's as much sexual politics in her content, perhaps, as in that of

Ani DiFranco but, like DiFranco, the cubbyhole fails to define her.

There s social consciousness, sure, and there's the boy/girl issues of

hetrofeminists and girl/girl issues of lesbians in the Women's music

genre but the overcast is humanist, personal and interpersonal.

Degrees of nobility in the quest for freedom on the part of

individuals sexually oriented outside of the mainstream will be argued

forever but the poetry produced in the struggle cannot be

dispassionately ignored. If guys can t enjoy women s music, it could

be argued, then maybe a rhythm & blues artist like Ray Charles should

never have listened to country & western. Ferron s music evades

irrelevant labels.

Much as her "Irish potato face" (as cited by one nerveless reviewer)

favors Gene Clark as much as Petula, Ferron s lyrics owe as much to

instinct as to intellect. Her curved and angled structures of thought

utter a sensitivity so intimate that they sometimes convey an

impression of not being "heard" in lyric as much as "overheard" almost to

the point of eavesdropping on prayer. Her poetic forms often expand

and repeat in wider orbit in their musical place as a song progresses,

building upon perspective, changing or shading a key word here and

there, adding detail instead of redundancy. Where a first verse leads

into a chorus with "And the cart is on a wheel," the second verse

elaborates "And the wheel is on a hill," and so forth; a device

strengthening the logical structure of progression.

She found her performance style as naturalistically as her writing

style and directly through it, as she explains; "I sing songs to get my

sentences out and my sentences are longer than a lot of people's who

write pop songs. Just trying to put poetry to music, meeting the

poetic meter, you just have to work with it, playing guitar, making

longer phrases even though you re finger-picking or whatever. And

then you find yourself in this little world..."

Notably absent in the sentiment of the great body of Ferron s work is

a sense of the sort of bitterness and intent which finds presence in

the women's movement's relish for the term "uppity." It has more to do

with identity than cause. The male-dominated history of the modern

recording industry, wherein corporate slugs treat young artists much

as Bram Stoker's Renfield feasts upon bugs in Dracula, gives DiFranco

and many others justified cause to found their own labels. Ferron,

with her own Cherrywood Station label, has also discovered this but

she speaks, even of the massive corporate labels, without acerbic

descent. Perhaps it is merely caution. Perhaps, like the categories,

she has transcended the anger to focus upon talents whose dimensions

even their author has difficulty grasping, much less a major record

label. Because she's one of a kind. Because she's Ferron.

"You know I was always the last to follow/And I made it a point to be

the first to laugh/ You know that kind of cool is kind of cold and

hollow/And you can write that in my epitaph."

Gary Alexander

is an independent journalist and scholar whose focus of

interests range through a variety of disciplines. Under various names,

he has written (and ghost written) upon history and current event;

science and technology, as well as music and the arts in books and for

national periodicals. While particularly attentive to the subtle and

complex impact upon cultural imagination and contemporary structures of

presumption which activity in the above mentioned topics tend to have,

Alexander treats his topics with a slightly more than occasional resort

to humor.

Posted on October 6, 2000

|