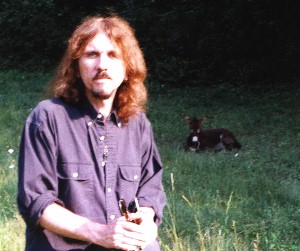

Tom Pacheco at The Colony September 1, 2001

by Irv Yarg

|

|

||||

A painting by Woodstock artist Anton Refregier [1905-1979] titled Gil and Jane depicts a long-haired, bespectacled young man giving solace to a disconsolate young woman. Behind them tattered posters adorn a wall with a "peace symbol" unobtrusively scratched onto it. Painted shortly after the killing of antiwar protesters at Kent State in 1973, viewers associated the image with that tragedy and, as Franklin Riehlman's profile of Refregier in the book Woodstock's Art Heritage points out, "the sorrow that attends the violence of war."

But, as Riehlman also observes, Gil and Jane were also friends of Refregier's son Alek, who had recently died in a motorcycle accident; a fact which gave the work an additional dimension of personal loss. A shallow and jaundiced eye may have seen the work as "a painting of a couple of sad hippies" while perhaps a more informed perspective may have discerned that, no, this painting is about something...

There is in this an analogy to the songs of Tom Pacheco, who will play his first full concert in Woodstock since 1998 when he appears at The Colony on the 1st of September. Having whet our appetites in the intervening years with the three or four numbers he might contribute as part of a local benefit roster, Tom will finally offer a full course serving to a Woodstock audience before he departs on a tour of Great Britain which will stretch into October. When he does so, you may be sure that what he brings to the table will not be found on a junk food menu. Like the paintings of Anton Refregier, they will be songs of substance.

|

|

As an art colony, Woodstock has been largely celebrated for its landscape painters. To be sure, there are numerous dimensions to explore and enjoy in such work, just as there are countless attributes to at least some of the music which flows by the minute from our radios. However drastically diminished the substance of that music may have become through the dramatically shrunken spectrum of ownership and interest brought into effect by the Telecommunications Act of 1996, there is still a trickle of songs about more than boy meets girl. It is apparent, however, to even the casual listener that songs of true substance are increasingly rare on the airwaves and, by substance, I mean those which reflect dimensions of human experience possessing a wider social significance.

This is a tradition of American music inherited by a precious few of today's songwriters directly from the legendary folksinger Woody Guthrie and it can still be heard in tunes like Bruce Springsteen's "The Ghost of Tom Joad." Guthrie wrote his own song for "Tom Joad" in his New York apartment the day after seeing Henry Fonda's portrayal of that character from Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath in John Ford's classic 1940 film. Guthrie had firsthand experience with the social and political fabric of that American reality and it's not difficult to imagine the impact that viewing must have had on him. It wasn't a date movie; it had real Substance.

We know that politicians can speak endlessly about issues of

substance without ever really saying anything. This, incidentally, makes

them easily the most pernicious "substance abusers" in the population.

But, when Pacheco deals with issues of substance, he does so with the

most human of philosophies and with the elegance and insight of a poet.

We know that politicians can speak endlessly about issues of

substance without ever really saying anything. This, incidentally, makes

them easily the most pernicious "substance abusers" in the population.

But, when Pacheco deals with issues of substance, he does so with the

most human of philosophies and with the elegance and insight of a poet.

Kenneth Allsop, in his book Hard Travellin', wrote about Woody Guthrie's "Homeric" pilgrimage through North America, singing on a common level about what he saw... "the building of the huge New Deal public utility project, the Grand Coulee Dam...about anti-fascism, about union-busting vigilantes with tear gas and blackjacks, about strikes and lockouts, about the homeless and unorganized and destitute, and about their loss of faith in what has been called `story-book democracy'." According to some current progressive opinion, television addiction, with its tightly-held definitions of social reality, the impact of DWI laws on the survival of night life, restaurants and meeting places, and other divergent social factors insure that the disenfranchised of today remain unorganized and that our comparison of world views remains largely confined to what happened on The Sopranos last night. Except, of course, for an oasis like The Colony.

Guthrie's own book Bound For Glory and his Dust Bowl Ballads gave us a moving and invaluable record of those times in American life because he knew the voice of the homeless, of the hitch-hikers and migratory workers; of the rail-riders with their worldly belongings in little piles in "Hoovervilles" around the country; of "Ladies cooking scrappy meals in sooty buckets, scouring the plates clean with sand. All waiting for some kind of chance..." as he wrote. You can find an echo of those street-level observations in Pacheco songs like "Turnpikes, Truckstops" or "Down the Promenade," snatches of life as gritty and real as those sand-swabbed plates.

The tradition was instilled in Pacheco before he began making his first public appearances as a youth in eastern Massachusetts. He carried it and developed it as he began his own American odyssey, swapping new songs in his McDougall Street apartment between the Cafe Wha? and a falafel stand in the mid-70s as other singers gathered, from Steve Forbert and Willie Nile to the Roches or Josie Kuhn and whomever else needed a spot in the wee hours to trade music and life experience.

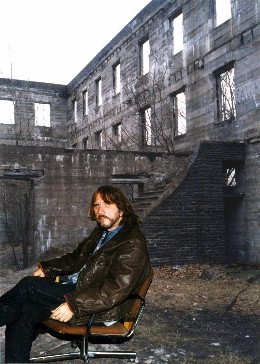

On his pilgrimage from Dublin to record his "Woodstock Winter" album at Levon Helm's studio, Tom was delighted to find a tree in the shape of an Irish harp in the yard of a house he rented for the stay. |

Another Woodstock artist, the late, great painter Edward Chavez, whose own paintings were not social or political in the sense of his contemporary Anton Refregier, once described to me the difference between technical skill in art and artistic "proficiency" by using an analogy a writer would easily understand: "If you have nothing to say," Chavez explained, "it doesn't matter how well you put the words together."

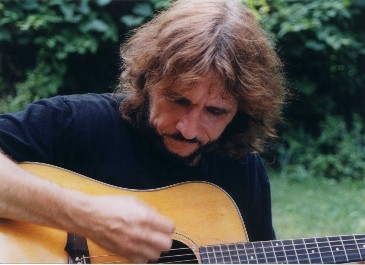

Tom's songs had substance from the very start; real human substance that you can hear even in his love songs, like the recent "There Was a Me Before There Was You." Rather than simply declare that "you make me hot, baby," they explore facets of intimate relationships with sensitivity and intelligence. But his range of subject matter knows no bounds. Recent tunes have been about an uncatchable fish, computers, schoolyard bullies, Che Guevara, sand (yes, sand), Neal Cassidy, Rosewell aliens, an old "Freedom Rider" from the `60's, a microwave tower and the story of a courageous girl, Julia "Butterfly" Hill, perched protectively for two years in a giant Redwood. The only thing you can be sure of in a Pacheco tune is that it will not be mundane.

This can present a problem with today's record companies. Pacheco will be meeting to speak with a new label on the upcoming tour but an option for an album with his last label was shot down by a fictional character. Here is where a shallow view of his work creates a distorted perspective. Tom had recorded a song about Teddy Roosevelt in which one of Teddy's Rough Riders calls him a fool, a line which is repeated in the chorus. Now, Tom has treated many historical characters imaginatively in song- from Vincent Van Gogh to Juan Romero, the busboy who cradled the head of a dying Bobby Kennedy, to Billy the Kid and John Wilkes Booth. But this one took a bizarre partisan twist when a larger corporation swallowed the label and its manager viewed the song with a distaste he felt was sufficient reason to not pick up Tom's option. To the previous CEO, the song was the best on the album but the new multinational owner thought it might be offensive to some Americans. Teddy Roosevelt, a fool? pul-eez...

This flavor of controversy is certainly not unknown to Woodstockers. Highly regarded local writers from Howard Koch to Howard Fast and others certainly felt the pinch of repression. The socially conscious Anton Refregier, who had won a national competition in 1941 to paint a 27 panel mural representing events in the history of California in an annex of the San Francisco Post Office, depicted scenes which reflected what some right-wing groups felt was a politically liberal outlook. Before he had finished in 1953, a resolution supported by the new Vice-president Richard Nixon sought their destruction. The periodical The Nation joked that Nixon thought he had been elected "Art Commissar" and artists federations fought successfully against the bill but the reflex is the same. In the Reagan years, Kristofersen did an amazing album in protest of what he saw as an illegal and murderous policy and was not only dropped from airplay like a stone but so frozen out at the corporate level that his recording career was history.

Pete Seeger is perhaps the best known folksinger to have been blacklisted in that era and it seems more like poetic justice than irony to note how the tradition comes full circle. A few weeks ago, Tom Pacheco played a concert in that little church near Stockbridge which became famous in a song and movie Alice's Restaurant by Woody Guthrie's son Arlo. The church has been fixed up grandly for concerts recently and is being maintained by the Guthrie family. Tom was one of the first artists to appear in the new venue and it was Pete Seeger's grandson, Tao Rodriguez, who called Woody Guthrie's granddaughter, Sarah Lee Guthrie, to say "Hey, this is a guy you gotta have at the church." A tradition lives on...

You can hear Tom's songs on albums by The Band, Rick Danko, Leslie Ritter & Scott Petitto and many other artists but only a few of Tom's own CDS are available in the United States. Some imports can be found from England or Norway by the diligent web surfer. A couple of his earliest can only be gotten from Japan but several will probably be available at the show.

-Irv Yarg

Irv Yarg is an internationally published observer on cultural and political events who resides in the Hudson Valley area. His analysis of the recent and ongoing musical history of the region will be featured as a part of our coverage of the local scene.