Just This Side of Legend

Just This Side of Legend

Story by Gary Alexander

Photos by Ray G. Ring IV

In

1964, the heyday of folk festivals and hootnannys, a young Bob

Dylan wrote a long 'folk letter' to a small music publication called

Broadside which touched upon topics such as career 'sacrifices

to conscience'. In particular, Dylan referred to the then current

folksinger's boycott of tv shows which still black-listed certain

performers.

"The heroes of this battle are not me an Joan...an the Kingston Trio

nor Peter Paul an Mary," Dylan wrote. But "people like Tom Paxton,

Barbara Dane, and Johnny Herald...they are the heroes..." By this he

meant that they stood to lose the most by missing critical exposure

while joining the boycott.

As Dylan went on to megastardom, other lights of the Village folk

scene, such as the 'heroes' he mentioned, have indeed fared otherwise.

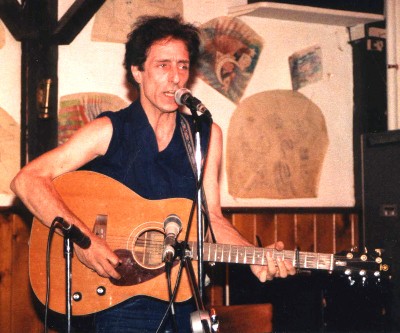

John Herald,

who originally came to public notice as a leader of the

bluegrass Greenbriar Boys, recording for Vanguard and Elektra Records

during the folk boom, has never lost that edge of tragi-heroic appeal

as a performer who retains a legendary stature among other musicians.

In the 1960's he often appeared as a backup (sometimes under the name

"Daddy Bones") on records by such stars as Ian & Silvia, Tom Rush, Doc

Watson, Buffy Sainte-Marie, and Ramblin' Jack Elliot. At one point he

briefly joined the folk-rock group Flying Machine just before James

Taylor left the band to set out on his own.

Ralph Rinzler, Bob Dylan, John Herald

(photo credit unknown)

|

In the 1970's, Herald recorded solo albums for labels like Bay Records

and Paramount, enlisting backup musicians of his own in a roll-call

sounding like a Who's Who of studio stars. Featuring country-scat

vocals characterized by high energy, often lopingly clever lyrics,

Herald also contributed stand-out tracks on the Woodstock Mountain

Revue series by Rounder Records.

Herald's delivery developed out of his early use of the bluegrass

idiom but he is quick to point out that the style he traditionally

intoned has not always been thought of as traditional bluegrass.

"Whatever I've been in has never been a traditional band," he insists.

"Perhaps now the Greenbriar Boys are thought of that way because we

used bluegrass instrumentation but we weren't doing only bluegrass

tunes. We might have done a Cajun tune, a Mike Nesmith song, a Woody

Guthrie song...One time that we played at Carnegie Hall there were

calls from the audience to 'Play Blue-grass!' So, that was certainly

recognized back then."

Former Cafe Expresso owner

Mary Lou Paturel & John Herald watch a

performance at Tinker Street Cafe in 1989.

|

One of the reasons the Greenbriar Boys eventually broke up, Herald

explains, was that at the time "the Beatles got going" he wanted to

try still more experimentation with their music while other group

members were reluctant to stretch it too far away from 'proven'

models. Herald's desire to be a bit more adventuresome in his

approach to music against varying degrees of resistance has become a

repeated theme in his career.

"I've had to go through that sort of war all my life," Herald claimed

with a grim little smile. "It's the great conflict now that I'm most

interested in pursuing a solo career. I do have my band and that's

where I get the majority of my work but you can't name on one hand the

northeastern musicians that have made it playing country music or

bluegrass. Yet, when Rounder Records wanted me to do an album for

them, I sent them a letter and said 'If I record for you, I'm gonna

want to do it my way and it's not necessarily going to be a

traditional record'; they sort of lost interest."

That kind of pigeon-hole resistance to change is also quite apparent

in the career of Bob Dylan, whom Herald remembers in the Golden days

of Village folkdom "before he had any hair on his face."

"All we heard was here was a kid from Minnesota who loved Woody

Guthrie," Herald recalled. "He used to do Guthrie impersonations and

before I ever saw him playing the guitar, he was playing the fiddle.

He had this black corduroy cap as a trademark and he covered a lot of

territory in those days. He'd be in somebody's store one minute, in

the Park the next..."

Herald saw a lot of Dylan in the early times, hanging out at Gerde's

Folk City or jamming in the dirt floor cellar dressing room of the

club. Their respective girlfriends were close and musician's haunts

limited. Dylan's first big break came when he opened for the

Greenbriar Boys and stole the bulk of Robert Shelton's review for the

New York Times.

Garth Hudson, John Herald, and Paul Geremia--

Garth Hudson, John Herald, and Paul Geremia--

Masters swapping licks at the Rosendale Cafe.

|

When Dylan and other New York folkies started making large waves with

their original material, John Herald naturally decided it was time to

work on his own songwriting and, in 1964, he moved to Woodstock full

time to do just that. Herald, whose poet father brought him to

Woodstock when he was a tyke, began to become a weekend and summer

regular in the early 60's and eventually a "doorway" who introduced

other keystone New York musicians to his retreat- including stickers

like John Sebastian. Spending much of his youth in boarding schools

and foster homes on farms, much of it in Bucks County, Pennsylvania,

Herald imbibed country life into his veins, calculating that he's

spent 4/5 of his life in the countryside.

While his tunes have been cut by people such as Linda Ronstadt,

Jonathan Edwards, Joan Baez, Maria Muldaur and others, the music of

John Herald remains a heroic struggle which still looks ahead for full

stardom. There's a new agent and manager now and a new album in the

works. There's also that same determination to keep the sound fresh

and exciting. The ones who can really do that and keep doing it

through the years; "they are the heroes..."

You can hear the John Herald Band at the Tinker Street Cafe on

November 17th [1990].

- Gary Alexander

Gary Alexander

is an independent journalist and scholar whose focus of

interests range through a variety of disciplines. Under various names,

he has written (and ghost written) upon history and current event;

science and technology, as well as music and the arts in books and for

national periodicals. While particularly attentive to the subtle and

complex impact upon cultural imagination and contemporary structures of

presumption which activity in the above mentioned topics tend to have,

Alexander treats his topics with a slightly more than occasional resort

to humor.

Posted on October 8, 2001

|