Triumph of the Exile

Triumph of the Exile

Story by Gary Alexander

Photos by Ray G. Ring IV

A Dazzling New Clayton Denwood CD Delivers on

a Long-Anticipated Promise

Before

a trapdoor opened and Clayton Denwood vanished from town as

suddenly as he had first appeared, he had been identified, during the

prior seven years, as a "Woodstock Musician."

Long familiar on the local scene and in a number of Manhattan

musical venues as an extraordinary writer and singer of songs, his

appearances in clubs and at concerts, solo or in company, marked him in

our minds as a regional artist of considerable ability. Everyone, of

course, knew that on a mandatory New World Order National ID card, his

nationality would be listed as "Canadian" but we thought as little of

that small detail as, apparently, did he. If you're in Woodstock long

enough, what does it matter if you're from Brooklyn, Kansas or Canada?

Woodstock Nation has its own imaginary national ID cards, doesn't it?

Nowadays, an ID card or a bank card can also serve as a disguise.

It once was that a supermarket clerk could take a measure of someone by

how they folded their money. Are the big bills on the inside or outside?

If they come out of pocket jumbled into origami puzzles, the bearer is a

poet, musician, artist, drunk or from some other existentially-inflicted

state.

In Clayton's case, the artist's existential dilemma was nurtured

and conditioned by Woodstock's matter-of-factly, day-to-day,

note-by-note creative preoccupations. Always a new song coming; always a

shift in schedule to make room to play an emergency community benefit or

join a jam that was forming as swiftly as a weather front. Details like

"origins" were continually flooded away by details of "now."

In Clayton's case, the artist's existential dilemma was nurtured

and conditioned by Woodstock's matter-of-factly, day-to-day,

note-by-note creative preoccupations. Always a new song coming; always a

shift in schedule to make room to play an emergency community benefit or

join a jam that was forming as swiftly as a weather front. Details like

"origins" were continually flooded away by details of "now."

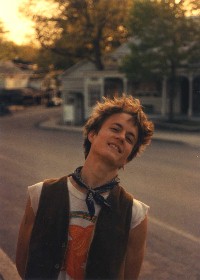

"Probably, for me, Woodstock is a place where every day has its

own quality to it," Denwood said recently in a phone call from Toronto.

"Being a small town, when you walk out the door, you're going to see

someone you know...which can change the course of the day. So, your

script is pretty much unwritten."

Denwood allows that similar diversions can happen in cities as

well, particularly along well-beaten cultural and occupational paths.

But, for all of its bustling population and professional comrades, he

finds the city lonelier and more isolating than the Woodstock he

remembers. He finds himself reflecting upon the beauty of the town, its

mountains and streams- "...a haven, in its own way, from the world," he

sighs.

Although his ancestral roots are somewhat tangled in American

soil, the Denwood line had returned to England before his father's

generation and Clayton himself was Canadian born. He can recall Beatles,

Beachboys and other standard musical fare of the '70's in his earliest

memories of home life and a small piano he began playing at eight when

his family moved to Chicago and inherited it as a piece of left-behind

furniture from a former tenant. The adopted piano remained in the

household and under Clayton's fingers when the family returned to

Canada.

Although his ancestral roots are somewhat tangled in American

soil, the Denwood line had returned to England before his father's

generation and Clayton himself was Canadian born. He can recall Beatles,

Beachboys and other standard musical fare of the '70's in his earliest

memories of home life and a small piano he began playing at eight when

his family moved to Chicago and inherited it as a piece of left-behind

furniture from a former tenant. The adopted piano remained in the

household and under Clayton's fingers when the family returned to

Canada.

Around the time the compact disk debuted, Denwood recalls

finding a horizon-widening treasury of vinyl LPS in milk crates

discarded by a neighbor. In roughly the same period, he followed a

12-year-old's urge to drums and a high school era band. By 15, he had

picked up a guitar and, within a year, started writing "little piano

songs." From there, it was just a matter of time before he outgrew his

role in the band and decided to form his own group in Toronto.

A decision to study in Montreal led to distraction, as he

remembers: "This was the first time I had an apartment. I had a big, old

Underwood typewriter there and I just spent most of my time writing. I

didn't concentrate too much on school and, by the time winter exams came

around, I remember sitting for a world politics test...about ten minutes

into it I just folded it up, walked out and never went back. Spring of

the next year, I left Montreal and came to Woodstock."

This was early 1992 and, actually, Denwood's sites were drawn

on Greenwich Village but the magnetic lure of this little town had

rubbed into him through books, magazines and legend just as it had the

unknown driver who had picked him up hitchhiking south in Vermont.

This was early 1992 and, actually, Denwood's sites were drawn

on Greenwich Village but the magnetic lure of this little town had

rubbed into him through books, magazines and legend just as it had the

unknown driver who had picked him up hitchhiking south in Vermont.

"You know, I've always wanted to see Big Pink, myself," this

fellow admitted in the middle of a conversation about Woodstock's

musical legacy. He was referring, of course, to the world-renowned

little house tucked away off of a minor road in Saugerties, pictured on

the back of the first album by The Band and recording site for most of

the legendary "Basement Tapes" they rolled off with Bob Dylan. That

called for an impulse exit from the Thruway and a fruitless search

around Saugerties before Denwood's driver gave up and deposited the

musician at the bridge near Tinker Street Cafe.

It would take him, Denwood recalls, "about a year" to find

Big Pink but he immediately found a scene in Woodstock which intrigued

him. Talent abounded in local artists such as Judy Whitfield, Paul

McMahon and numerous other performers and, at the time, as he recalls,

"Hothouse Flowers were in town making a record. So was Natalie Merchant

and other folks. It just seemed like a good place to be for a little

bit."

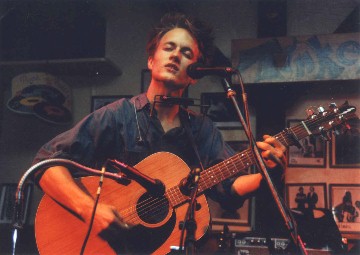

Within days, Denwood had electrified the crowd at the Cafe's

"open mike night" and word circulated swiftly that there was a "New

Dylan" in town. He continued creating a sensation in subsequent

appearances. For one thing, he was just too young to be that good.

Within days, Denwood had electrified the crowd at the Cafe's

"open mike night" and word circulated swiftly that there was a "New

Dylan" in town. He continued creating a sensation in subsequent

appearances. For one thing, he was just too young to be that good.

Many of you know the story from there. Clayton stayed,

working hard at his craft, producing gem after newly-written gem for the

performances he polished zestfully as he strove to live up to that "New

Dylan" image. It was an unfair label which invariably disappointed but,

in Denwood's case, unavoidable.

Even as his musical acumen grew, his presence and poise-

his songs and delivery- his natural style and manner remained distinctly

Dylansque. His onstage intensity was an adhesion to seize audiences and

his voice, even at its most raw moments markedly better than Dylan's own

- with perhaps a hint of Jimmy LaFave tonality- was progressively

untethering its melodic binds and expanding its grasp of subtleties. The

flashes of power in his songs forecast enough promise to anticipate some

true masterpieces down the line and he even had the opportunity to play

with members of The Band who left that fork in his road.

Denwood settled in, picking up odd jobs between gigs to

keep just enough of those crumpled bills in his pocket to make due as he

focused on the next tune. Along the way he married a lass from Columbia

County and fathered a son he wanted to bring to Toronto to meet his

grandparents. There wasn't a second thought that a simple trip north

could lead to the complications which have made him an exile from his

adopted hometown.

"Originally, I was quite insulted and indignant," Denwood

said of that frozen moment border guards blocked his return to the

United States. "Why would you do something like that to me? I can't

remember the official charge exactly- that I lived there and worked

without letting anyone official know or something like that- I'm not too

involved with the government or anything- I've got the papers on file.

It wasn't a tax thing. I think what they were most pissed off at,

basically, was that I didn't pay attention to the rules. I just did my

own thing."

Barred from entry for five years, Clayton will not be

eligible to return until August 19, 2004- two days before his 34th

birthday. In the meanwhile, he gathered a band of crackerjack Canadian

players, recorded his first album live at Toronto's Old York club and

issued it as "The Exile Sessions." A soaring blast of

rock-away-your-blues originals served with self-possessed authenticity.

Barred from entry for five years, Clayton will not be

eligible to return until August 19, 2004- two days before his 34th

birthday. In the meanwhile, he gathered a band of crackerjack Canadian

players, recorded his first album live at Toronto's Old York club and

issued it as "The Exile Sessions." A soaring blast of

rock-away-your-blues originals served with self-possessed authenticity.

Sunset on the Highway |

More recently, Denwood's first studio album, "Sunset on

the Highway," produced by popular Canadian guitarist Joe Dunphy, emerged

as even more of a stunner. Melodically matured and absent the occasional

arm wrestle between lyric and melody which slowed a few of Denwood's

earlier works, here, an internal consistency is at ease with the mating

as lyrics provide opaque tricks and truths with the unpretentious code

of a righteous seeker. Master Dylan could well have written Denwood's

opening track, "Only You," during one of his endless phases of self-

reinvention. But he didn't and, for all of its Dylansque quality,

Clayton claims it as pure Denwood.

On "Make Me Whole," Denwood finds some of his own doors to the

secret garden and seems to reflect, between the lines, the puzzlement of

someone overshadowed by the might of American culture but still

considered an outsider: "Be my comfort in confusion; be my refuge from

laws of men/& I will be the ashes where your faith can rise again/Be my

guardian of innocence; be the forgiveness of my guilt/& I'll be the

foundation where your dreams can be rebuilt/For careless are the raging

seas & so blinding is the light/we must cleave to one another if we hope

to make this flight/I'm not asking you to surrender to any flag upon a

pole/It's just that I am almost free and your love will make me whole."

Throughout the album the musicianship turns up top of the line.

The delicious, engaging drum work of Josh Hicks positively shines on

tracks like "King of His Own Hometown" and Larry Johnson's pedal steel

on "Real Thing"shows us that Nashville North has more bite than the one

in Tennessee. The title tune is not as "country" as "Sweetheart of the

Rodeo" and the shuffling rocker "Sorry (if I love you)" owes more to

Chuck Berry than Bobby D. But, not to be bypassed, we find some of the

poetic suspensions Dylan discovered at the Gates of Eden in

"Sanctified."

In "Downstream," which might have been a bid for a 'single' in an

overtly commercial scenario, Denwood blends in some chords which are

more obviously pop-oriented than other frames he fleshes out here and

turns them to task a broader vision. It's a song I don't think Dylan,

for all of his genius, could have written - even in the days he was

competing with the Beatles- and may have represented a profitable

retrogression of sorts for Clayton. Otherwise, his efforts provide

guidance for roots instinct in a contemporary American music which is

currently a bit at sea and at danger, depending upon where the New World

Order corporate music capital decides to locate, of becoming part of

Canada. (This, of course, will be installed- as the globe warms- along

with palm trees in Winnepeg.) Altogether, for card-carrying Woodstockers

as well as New Worlders without lines across their musical roots,

the album is sparkling reward to Denwood fans who have missed

his presence locally and can be found in a few regional shops like

Rhythms in Woodstock or on the web at online CD stores like cdbaby.com

or cdstreet.com.

Meanwhile, Clayton bides his time playing occasional "above

upstate" gigs, helping friends build things (such as the studio his album

was recorded in) and playing hockey with a team called the Hawks. (The

team's name provokes daydreams of the legendary Ronnie Hawkins- whose

old band was called The Hawks before they became The Band). He sends his

love to us all back here as he waits it out and his thoughts stray daily

southward. His former wife, a country girl uncomfortable in Toronto,

left for Florida with his son and remarried. Although they remain on

friendly terms, he bemoans the difficulty of a telephone relationship

with a four-year-old...and he keeps seeing the slopes of Overlook when

he closes his eyes.

Meanwhile, Clayton bides his time playing occasional "above

upstate" gigs, helping friends build things (such as the studio his album

was recorded in) and playing hockey with a team called the Hawks. (The

team's name provokes daydreams of the legendary Ronnie Hawkins- whose

old band was called The Hawks before they became The Band). He sends his

love to us all back here as he waits it out and his thoughts stray daily

southward. His former wife, a country girl uncomfortable in Toronto,

left for Florida with his son and remarried. Although they remain on

friendly terms, he bemoans the difficulty of a telephone relationship

with a four-year-old...and he keeps seeing the slopes of Overlook when

he closes his eyes.

"I would be back in a heartbeat, if I could," the expatriate

said but betrayed a touch of ambivalence about the prospects of being

allowed through the checkpoint when the time comes. "I haven't really

challenged it. I could, if I knew who to contact. Chances are I could

make a pretty good case but it's hard to know where to send that kind of

appeal...and undoubtedly expensive. At least they can't stop my thoughts

from crossing the border."

-Gary Alexander

Gary Alexander

is an independent journalist and scholar whose focus of

interests range through a variety of disciplines. Under various names,

he has written (and ghost written) upon history and current event;

science and technology, as well as music and the arts in books and for

national periodicals. While particularly attentive to the subtle and

complex impact upon cultural imagination and contemporary structures of

presumption which activity in the above mentioned topics tend to have,

Alexander treats his topics with a slightly more than occasional resort

to humor.

Posted on February 22, 2002

|